In dual labor markets, workers can start their career on an open-ended or a fixed-term job. Does the entry contract have any persistent effect on labor market attainment over time?

There is a large body of evidence on the long-run effects of labor market entry conditions. In most cases, it is focused on business cycle fluctuations and it finds persistent negative effects on income and occupational attainment for those who enter the labor market during downturns (Kahn, 2010; Oreopoulos et al., 2012; Brunner and Kuhn, 2014; Altonji et al., 2016; Fernández-Kranz and Rodríguez-Planas, 2018; Schwandt and Von Wachter, 2019; Bentolila et al., 2021; Acabbi et al., 2022). Another, more recent strand of research documents the role of workers’ first employer, finding that initial matches with larger firms – or, more generally, with high-growth firms – have positive and substantial effects on long-term outcomes (Arellano- Bover, 2020; Gregory, 2020).

We conjecture that the degree of job stability at labor market entry and during the first few years of a worker’s career could have implications that are as important as those related to firms’ characteristics or to business cycle fluctuations. First, obtaining a fixed-term job as an initial employment opportunity may negatively impact the rate of human capital growth over time. Employment under a fixed-term contract, as opposed to an open-ended contract, is associated with an increased probability of transitioning to unemployment – resulting in direct consequences in terms of diminished on-the-job learning opportunities – as well as a lower availability of workplace training (Cabrales et al., 2017). Furthermore, for individuals with limited financial resources, the heightened risk of unemployment faced under fixed-term contracts could lead to suboptimal long-term decisions. Specifically, fixed-term workers at risk of becoming unemployed may opt to accept lower wages and/or any job offer, even those for which their skills and experiences do not align with the requirements. In equilibrium, these phenomena could subsequently hinder opportunities for career growth, as young workers may choose to forgo prospects of lower earnings growth in favour of achieving greater job stability – that is, securing an open-ended contract.

These drawbacks notwithstanding, fixed-term jobs also offer several advantages for young workers. First, their typically short duration enables frequent transitions between employers, allowing young individuals to gain experience across diverse sectors and work environments. This is particularly beneficial for less-educated workers, who can use these opportunities to offset limited formal education with practical experience in the labor market. Second, fixed-term contracts facilitate the swift termination of unproductive matches with minimal frictions, unlike open-ended contracts that involve severance costs for employers and may align with workers’ preferences for job stability.

To study the long-term effects of the type of initial contract, we analyse a sample of young workers aged 16 to 29 who are entering the labor market for the first time, starting from 2005. The data source is the Italian Social Security Institute (INPS) administrative records, which cover the entire population of Italian employees. We construct a balanced panel of workers and follow them over the first ten years of their careers, which may include non-employment spells. In our sample, approximately 35% of workers begin on a fixed-term contract, while the remaining 65% start with an open-ended contract. The sample excludes those who initially entered as apprentices or contractors – around 50% of new entrants – whom we analyse separately.

We begin by documenting how yearly income evolves over the first ten years of their career, distinguishing between workers who started on fixed-term and open-ended contracts. We achieve this by utilizing the rich information set provided by population administrative data, which allows us to compare the income trajectories of individuals with similar demographic characteristics who start their careers in comparable firms – in terms of size, productivity, and company age – and at the same point in time regarding age and calendar time.

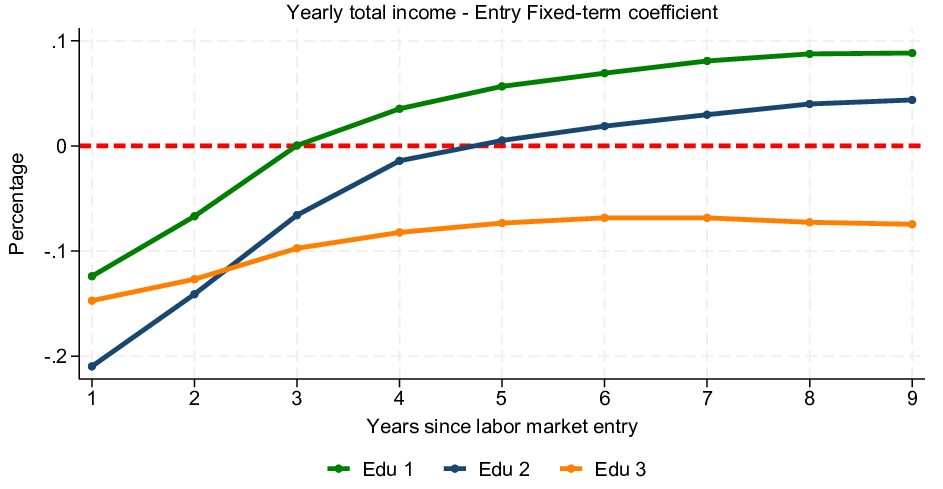

The results indicate that workers who begin their careers with a fixed-term contract initially report lower gross annual salaries compared to those who start with an open-ended contract. However, already after the first year in the labor market, we observe a convergence process, characterized by relatively more pronounced salary growth for those who entered with a fixed-term contract. This salary convergence process is not uniform across different groups of workers, depending on their level of education. In particular, workers with lower levels of education experience more pronounced salary growth that exceeds mere convergence. By the fourth year after entering the labor market, these workers report higher annual salaries compared to those who entered with an open-ended contract. In contrast, highly educated workers are, on average, disadvantaged by starting with a fixed-term contract, although a partial convergence process is still evident.

To better understand the dynamics behind these results, we decompose annual salaries into two determining factors: weekly wages and the number of weeks worked during the year, both in full-time equivalent terms. This analysis reveals that the trend in the wage gap between the two groups of workers over time is almost entirely explained by the amount of time worked, with only a marginal difference in weekly wages between the groups. Given that the incidence of part-time work remains relatively constant over time in both groups, these results indicate that the convergence in annual salaries primarily results from workers entering the labor market with fixed-term contracts initially working for a relatively lower number of weeks during the year – i.e. initially spending more weeks over the year in non-employment. Over time, however, the number of weeks worked increases, eventually exceeding the amount of time worked by those who entered with open-ended contracts.

These preliminary results suggest that low-educated workers entering the labor market with fixed-term contracts can achieve relatively higher annual salaries over time, mainly due to greater job stability – or, in other words, a lower risk of experiencing non-employment. In contrast, workers who enter the labor market with open-ended contracts initially report higher annual salaries, but by the fifth year, this outcome is reversed due to a greater risk of spending time in non-employment for these workers.

We plan to strengthen our empirical evidence by using an instrumental variable approach, exploiting regional and time variations in the share of open-ended hiring. While we account for a broad range of individual and firm-level characteristics at entry, this additional analysis is essential due to the potential influence of unobserved individual factors. These unobserved characteristics may affect both the selection into entry contract types and income trajectories over time. However, for these factors to challenge our findings, they would need to imply that workers with stronger long-term income prospects are more likely to begin their careers in fixed-term jobs – a claim that runs counter to the existing empirical literature.

To conduct counterfactual policy experiments, we develop a search and matching model in which workers balance job stability against long-term earnings growth. In this framework, a worker’s productivity in a given job is unknown at the outset and becomes clearer with job tenure (Jovanovic, 1979; Faccini, 2013). Workers remain employed in positions where their ex-post productivity is relatively high, while they exit quickly from jobs where their productivity is low. In this context, low-quality matches should dissolve rapidly. However, frictions may prevent the swift termination of certain matches. In particular, open-ended contracts generate inertia for both firms and workers: termination is costly for firms, due to severance payments, and workers may value job stability even in low-productivity matches. By contrast, fixed-term contracts can be ended at lower cost if the match proves to be of low quality, meaning that they are not subject to the same frictions, allowing for quicker exits from poor matches.

In this framework, the longer workers stay in poorly matched jobs, the worse their re-employment prospects become once the match is eventually terminated. This is due to both a lack of accumulated labor market experience and a declining job-finding probability over the life cycle. Using this theoretical model, we aim to replicate the empirical findings presented above and evaluate counterfactual scenarios.